Aspen Art Museum

BOLD AND BEAUTIFUL

ARIA DEAN

I was born and raised in Pasadena, California. I grew up in a production family: My dad’s an assistant director, my mom’s a producer. All of their friends were in the industry and it was the height of the music-video era and MTV. I worked as a costume assistant when I was in college, but my parents really encouraged me to find my own interests. I always did art stuff. I painted, drew and wrote a lot as a kid and I ended up going to Oberlin College. I studied art and philosophy and just stumbled into the art world and went on to work in numerous places in my 20s.

COLLEEN BELL

I’ve been in Los Angeles for 32 years. I went to college in Virginia, with a spell at St. Andrews in Scotland. I was working on Capitol Hill and I had traveled to various places in the world, but I had never been to California. Then I re-met my childhood sweetheart who was in LA launching a new soap opera, The Bold and the Beautiful, and he proposed marriage right away.

The show was just getting off the ground, so it was all hands on deck and, although it felt a little off my career trajectory, I went to work for the production company. So, I was producing and my husband was a head writer. This was the moment that the international markets were opening up, and we found that soon our little half-hour daytime drama was being seen in 110 countries around the world, with over 150 million viewers.

The social activist in me thought, “Wow, what a platform to educate people, build social cohesion, and to promote peace and prosperity.” To give just one example, we had many viewers in Africa and it was when the AIDS epidemic was raging through the continent. We would tell these long story trajectories, weaving in information about HIV prevention.

When we had our fourth child, I decided to take a leave of absence and asked myself what I had always wanted to do but hadn’t had time to pursue, and that was to work on toxic chemical reform. The NRDC [Natural Resources Defense Council] was doing the best work in the nonprofit space on this, and so I reached out to them and offered to volunteer. They sent me to Washington, D.C., where I met Senator Barack Obama in the second month of his first term. Then one thing led to another, which brought me back into government work. I was with the Obama administration and my final position was as the US ambassador to Hungary.

Now I work for the Newsom administration, in the governor’s office of business and economic development as the director of the film commission. I am happy to be working somewhere where I feel like my values completely align. This is a state of dreamers, somewhere that doesn’t only recognize but celebrates our cultural and ethnic diversity as one of our great assets.

I love being in California.

AD

Yes, lately I’ve been missing California more than ever, not just the sun but the California attitude, the way people interact.

CB

There is definitely a large community of creatives here. And something I’m excited about at the moment is this even stronger belief that art and film have the ability to build social cohesion, promote peace and unify people around the world. With my portfolio as film commissioner, I’m not making the films, but I’m taking great pride in all of the extraordinary content being created in film and television here in California. It gets beamed all over the world and keeps Californians working, doing the jobs that they love to do.

I think our country, unfortunately, is experiencing a moment of such deep polarization. But in a museum or movie theater, we’re all there experiencing art and enjoying the opportunity to be together.

AD

On a personal level, my focus right now is on finding a way for art and film to really exist together. For the last six, seven years, I’ve been making video work and sculpture largely in the context of the art world. Last year, I made a short film that finally had a life both in the art world with exhibition formats and also on the festival circuit.

I am interested in reaching a wider audience, and digging more into the language of film. What it can do, what it can make people feel, is very exciting to me. But they’re not mutually exclusive industries, there’s a way to really straddle both and to make things that can live in both spaces.

CB

Film has the ability to provoke conversations about pressing issues such as poverty, war, racism and gender inequality. My cousin, Bradley McCallum, is a conceptual artist and social activist. He addresses trauma and struggle and racial identity. His work includes large public projects, sculpture, video and photography. I’m inspired by what he’s doing at this moment in time, mixing all of those disciplines together to address some really pressing issues. Incidentally, I went to the Ed Ruscha opening at LACMA last night, and it felt like such a powerful California experience.

AD

It’s funny, Ruscha is alive and well, of course, but I have a tendency to be very influenced by a lot of dead white men. My all-time favorite artist, although I cooled on it a bit, is Robert Morris, who passed away a few years ago. He was known for hard-edged minimalist sculptures, but through performance, video and film he also really engaged with his own subjectivity as a white American man, inhabiting caricatures of the gangster, the cowboy, the intellectual. A lot of this work was happening during Vietnam and the anti-war and labor movements in New York City, and he was actively organizing artists in relation to these through projects like Art Strike. I think he’s a reminder of how one can not only comment on or work through political stuff in one’s work, but also be part of a community of people thinking about those things.

A really early love of mine is Senga Nengudi. She has been a sculptor since the 1970s and raised interesting questions about making abstract work as a Black woman and about what it means to make art as a Black person in America. What are you supposed to be doing? Are you supposed to make figurative work? Is abstraction a tool that is interesting or useful?

I’m also really influenced by a lot of maybe dry, experimental film work from the 1960s and ’70s, like that of Michael Snow, who passed away last year. Stuff that may seem very dull to watch but is riveting in some ways.

Also Tiffany Sia, a great artist and filmmaker who did a lot of work around the Hong Kong protests a few years ago, and is interested in the histories that involve China, Hong Kong and activism. We’ve been talking to each other a lot lately about ways to look at history and incorporate specific and perhaps lesser-known moments into filmmaking in the art world.

CB

I’m inspired by Judy Baca—by her large murals, how she brings together members of the community to participate in the experience of making art, and her depictions of California. I also think the work of Louise Bourgeois is extraordinary. I was reading a book about her recently: she’d have to wait until her kids went to sleep at night to go into her studio and make her art. It’s something I can relate to, being a working mother of four kids.

I write a lot, including a lot of speeches. When the kids were little, I would write at night: that’s when the house was quiet and I could make a cup of tea and get creative. They are older now, but those quiet, productive moments after very busy days are a nice memory.

AD

In television, I’m a religious watcher and re-watcher of the show 30 Rock, with Tina Fey and Alec Baldwin, which is maybe random, but I watched it as a kid and I watch it all the way through probably once, or maybe even twice, a year. I think it has some of the best writing in television, and most inventive narratives. It’s full of riddles.

On the film side, I’m really interested in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s career. His films ask aesthetic and political questions about the history of popular and arthouse cinema and melodrama, and the way the state interacts with the media; he wraps all this in interest- ing, personal narratives. I also really love the Korean filmmaker Hong Sangsoo, whose films are almost like little drawings of people hanging out.

CB

For me, Quentin Tarantino is an extraordinary filmmaker. He’s so pure in his approach and his characters are rich and complex. He’s going to be shooting his tenth and, he says, final project, here in California. It’s in our film and television tax credit program, which I administer.

I think Greta Gerwig’s approach to filmmaking is so clever, creative and bold. Barbie was a marvel in so many ways. It really got people back into the theater.

AD

I finally saw her Little Women. I feel like there are few films made today that I would call delightful, but that is one of them.

I am curious to know more about the film and television tax credits you mentioned.

CB

Well, there’s a lot of competition out there for California—many places in the US and other countries that are trying to lure production away from here. So, we are always asking how we can improve our competitiveness, and one way is our film and television tax credit program. One of the primary deciding factors for executives when choosing where to shoot is whether or not they’ll be able to receive tax credits. So, this is really an economic development tool to encourage productions to stay in California, which, of course, then translates into job sustainability and economic growth.

AD

I am interested in various tax credit structures, and I know very little about most of them. In the film industry, people are making budgets and contracts and getting permits, while this is all so vague and unclear in the art world. When I was working in development at an artist’s film company, it was the first time I realized the disparity and just how unstructured the art world is in terms of financing and even contracts. The distribution and rights structures in each industry are also very different in a way that I find fascinating.

CB

In the entertainment industry here in California, there’s a lot of policy and legislation that supports the growth of the community. Also, you have all of the labor unions that are advocating for the various groups.

At LACMA, we’ve undergone a major new building project and capital campaign. We had set ourselves such an ambitious goal, and it has been really wonderful how many people from all different sectors have come out in support, recognizing that bricks and mortar still count and that people want a place where they can come together and have a shared experience. That, I think, bodes well for the future of institutions.

AD

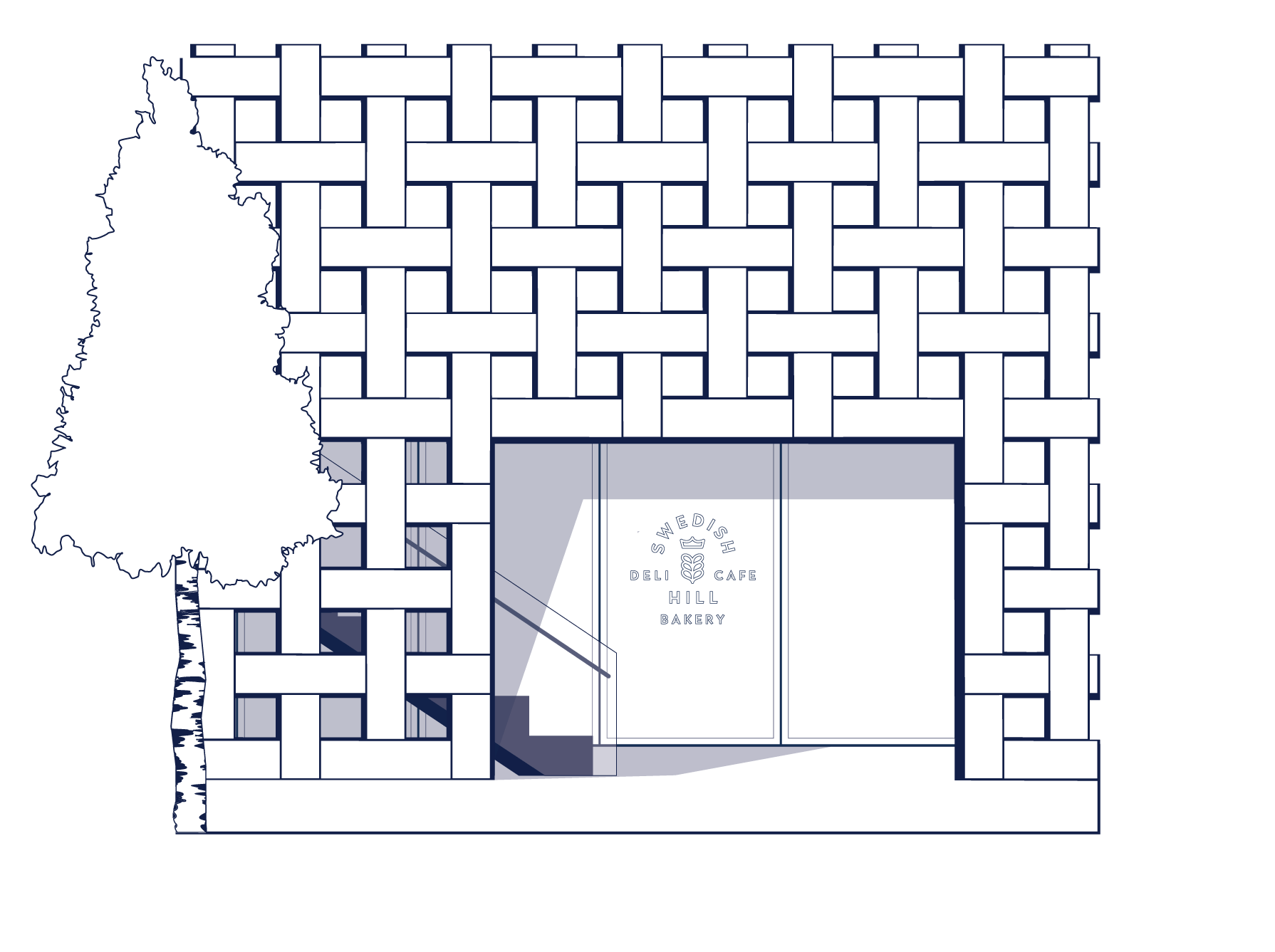

I went to Aspen for the first time a few months ago to give a talk about John Chamberlain at the Aspen Art Museum. I had no idea what to expect, but it was just so beautiful and calming. And the community there, especially at the museum, was equally nestling—so warm and welcoming. Very rarely when I give a talk somewhere do I think, I want to go back there, but it was so amazing. What a cool place to have expansive conversations! I feel like it’s the perfect place for that.

CB

We go way back with Aspen. My dad, who’s 84, still skis Aspen Mountain and hasn’t missed a season there since 1954. Aspen is my happy place. We have a house right on the river and with all those negative ions coming off, it’s the most relaxing place for me anywhere in the world. And, of course, I love the community. It’s international and the people living there, both full- and part-time, all come together to support music, film, art and sporting events. You get everything you need in one small town and there’s never a dull moment.