Aspen Art Museum

- Categories

- All events

- Talks and Lectures

- Member Events

- For more information on how you can join the AAM, please visit the Street Level Visitor Information Desk, inquire in the Shop, or call 970.925.8050.

- Swedish Hill Aspen is open on our Rooftop from 8AM–3PM

- Aspen Art Museum is an artist-founded institution dedicated to supporting artists in the development of bold ideas to shape our museum and the field of art today.

Jamieson Webster on Art, Archaeology, and Psychoanalysis

Aug 10, 2024

10:00 AM

Aspen Art Museum Rooftop

Listen to the Talk:

In conjunction with the current exhibition In the House of the Trembling Eye, the Aspen Art Museum hosts a presentation by psychoanalyst and author Jamieson Webster. Key themes and metaphors underpinning the exhibition—from the volcanic eruption to the flame of desire and the figure of Gradiva—provide a departure point for Webster to address wider connections between art, archaeology and psychoanalysis in the framework of her recent and current work on hysteria, movement and breathing.

Jamieson Webster is a psychoanalyst in New York City, she teaches at The New School School for Social Research, and is a regular contributor to New York Review of Books, New York Times, and many psychoanalytic publications. She is the author most recently of Disorganisation and Sex (Divided, 2022) and the forthcoming On Breathing (Peninsula UK and Catapult US, 2025).

Read the Transcript from the Talk:

Thank you so much to the Aspen Art Museum for having me here. Thank you to Daniel and to Jacqueline, especially. I had a great dinner with them last night, and it was also wonderful to speak with Allison Katz about her show. As I’ve been saying to everyone, I was sifting through all the material of the show. If you’ve been through it, it’s voluminous. It’s amazing. You can read about every single work, you can read about the relationships between them. You can read about Pompeii, and it was another thing to come in person and finally see it, which was incomparable, I have to say. And it’s very rare that I have that experience. I mean, I often have to look at an artist’s entire body of work, and then I go to the studio and I see the work, and there’s obviously a different experience of seeing the work in person, but this show blew me away. And I think that it’s a very rare show to put this kind of work over centuries together and to have the eye of an artist curating it in the way that she did with her eye. So it was really extraordinary.

When I spoke with Allison, she just told me how important psychoanalysis is to her and to her conception of art making, and that’s why she wanted to invite me. And I said, what do I do? And I said to her that as I looked at the work and as I looked at what was important to her and the various kinds of, I would say unconscious transformations, formations, creations, that there’s something about the very basic building blocks of psychoanalysis that felt very important to maybe talk about. So that’s what I wanted to do, which means that this is kind of like a masterclass in psychoanalysis. And I was like, ‘Does Aspen want that at 10:00 AM on a Saturday morning?’ And they were like, ‘Go for it.’

So that’s kind of how I’ve conceptualized it and I’ll tie it back to her work. I couldn’t tie it to all of the work in the show more generally, but I kind of focused on her work because it’s her as an artist that is the mind behind this. So I kind of got interested in that idea. And the first thing that I would say is in the unconscious, there’s no time according to Freud, meaning that everything can exist at once. Every aspect of time can exist in the same space. And there’s something about this show where that’s very, very palpable. And you have this occasion to see a Pompeii fragment next to a contemporary piece of art, next to a piece of art that may be from a generation before you, and to see the way that they echo between each other. And I found that very stunning.

And the other aspect for it about the unconscious is he says that it’s the closest to what he calls “Perceptual Reality.” And what he means by that is that not everything that you experience makes it to consciousness. And by the time what you experience makes it to consciousness, it has to take quite a lot of roads. And so at the end that he says is closer to perception, is closer to the unconscious, which is a much more heightened, almost psychedelic reality, which is also the reality that you experience in dreams, right? I mean, why are dreams so vivid? Why are they so emotionally fraught? Why are they so intense in a way that reality sometimes isn’t? I mean, it can be, but for the most part it isn’t all the time. And you have a quality there of what it means to make art be closer to this unconscious side of reality.

And the other thing that we understand about the unconscious is that everyone in their unconscious is a genius. Freud said this, no, really everyone’s a genius. Everyone’s an artist. I mean, there’s something about what your unconscious does that’s incredibly creative and unique and singular. And I love this because for me it means that there’s something very democratic. Not everybody can make art. And Freud, he was very particular about this, he says, not everybody has the capacity for these kinds of sublimations. And that’s true. I mean, I will never be a musician try, though I may. But there is something interesting about the fact that you can have a musical sensibility in your own consciousness.

And what’s also important about this is while this is your individual reality as sifted through your psychic life, it is both an incredibly local affair. It’s you, your history, where you were born, when you were born, what you’ve been exposed to. But for Freud, this also reached much further that into a universal landscape of culture and history. And he felt that that was true for everyone because we all have to take in the symbolic world that you get to reach down to the beginning of time. And it’s around this sort of idea of the unconscious that he developed the Archeological Metaphor. Freud said that he had more archeology books than he had psychology books or philosophy books, and it was true. And he liked to show his erudition with respect to archeology all the time. You’ll find these huge passages where he shows you that he knows how they uncovered in Italian town and all of the strata of history that are buried, and he’ll just show off in this respect. But it was very important for him because he felt that in the work of analysis, you’re doing a kind of archeological dig, and that in this work you see cycles of eruption, creation, destruction as they’re present in each one of our individual psychic lives. And I really love in particular the phrase that he said, that doing the work of analysis is ‘making stones speak.’

So today I’m going to talk about formations of the unconscious, but I took this picture as my inspiration. You can see the text for shifting variations of Katz’s own moniker are threaded throughout her AK Graph paintings, here her name and facial features appear as a slogan. All is on. ‘Over a vista of Vesuvius erupting, the volcanic ash cloud obscuring the Azure sky. A second self-portrait appropriated from an earlier work occupies the center of the artist’s forehead, bridging an understanding of eruption as a geological process and a metaphor for creative acts.’ So I took this as her kind of statement about what it means to be an artist and create and this kind of archeological historical reality that’s in the mind of the artist, and that obviously inspires this show.

Okay, so we’re going to start with Eruption. So Freud has three of his first large works. It’s the “Interpretation of Dreams,” “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life,” which is the Freudian slips, and then “Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious.” And many people forget that he started with dreams, jokes, and slips. He wants to create a whole new science. He wants to create a whole new medical cure. He wants to create a whole new idea of what it means to have a psyche. And he starts with dreams, jokes, and slips. And throughout these books, part of what you see is that he’s incredibly anxious about the fact that he’s going to be a complete laughing stock for doing this. Like who on earth is going to take this man seriously? But I think that’s the beauty of the project. And in each one of these, there’s a different kind of unconscious formation that I think speaks to art creation and that’s what we’re going to go through today. So here we go.

The “Interpretation of Dreams” was written in 1900, and every single one of these books starts with what he calls an ‘Inaugural Example.’ So he goes through all kinds of jokes, he goes through all kinds of errors, he goes through many, many of his own dreams, but he wants to find the one that he’s going to show you in full how his method works. And these examples are incredibly telling, and they tell an incredible story about someone on the precipice of making the kinds of discoveries that he made, inventing an entire discipline, and having to use his own mind, his own life to do so. He hides a lot of stuff, and of course the historians have poured over every little detail and what he’s sort of not saying or what’s in there, what was going on in his life that we now, and I’m going to tell you a little bit about this story as behind these ‘inaugural examples.’

So this is the first one, and this is the dream that he says is his ‘Specimen Dream’ that he’s going to analyze in full. So this is “Dream of July 23rd, 24th, 1895,” and he says, ‘A large hall, numerous guests whom we were receiving among them was Irma. (Irma was his patient.) I at once took her on one side as though to answer her letter and reproach her for not having accepted my solution yet I said to her, if you still get such pains, it’s really only your fault. She replied, if you only knew what pains I’ve got now in my throat and stomach and abdomen, it’s choking me. I was alarmed and looked at her. She looked pale and puffy, and I thought to myself that after all, I must be missing some organic trouble. I took her to the window and looked down her throat and she showed signs of recalcitrance like women with artificial dentures.

I thought to myself that there was really no need for her to do that. She then opened her mouth properly and on the right I found a big white patch. At another place I saw extensive whitish, gray scabs upon some remarkable curly structures which were evidently modeled on the terminal bones of the nose. I called in Dr. M and he repeated the examination and confirmed it. Dr. M looked quite different from usual: he was pale, he walked with a limp, and his chin was clean shaven. My friend Otto was now standing beside her as well, and my friend Leopold was percussing her through her bodice and saying she has a dull area low down on the left. He also indicated that a portion of the skin on the left shoulder was infiltrated. I noticed this just as he did in spite of her dress. M said, 'There’s no doubt it’s an infection, but no matter dysentery will supervene and the toxin will be eliminated.’ We were directly aware two of the origin of the infection, not long before when she was feeling unwell, my friend Otto had given her an injection of a preparation of propyls: propyls, proprionic acid, trimethylamine. I saw before me the formula for this printed in heavy type. Injections of that sort ought not to be made so thoughtlessly, and probably the syringe had not been clean.‘

Alright, what is going on in this dream? So one of the first things that Freud shows is that to analyze a dream, you have to take every single detail and you have to associate to it. And so he does this. So you have like six pages of association to every single aspect of the dream. What’s amazing is that once you have this picture of the analysis, all of the thoughts, all of the memories, all of the little bits of things that are behind the dream, you have a very, very small dream and you have a huge text, and he got interested in this sort of expansion and condensation that is part of the dream work. How does a dream take all of this and condense it into what’s fundamentally an image? All of this symbolic material, it condenses it into an image. I mean, this is an incredible act of the mind.

The next thing that he goes through, what you see in his associations to this dream is that it starts with this huge hall and there’s something very spatial about it. He’s welcoming everyone, they’re all coming over. He’s the doctor. And then it narrows down to one figure, Irma, he takes her over to the window, it’s him and her. He says, 'What’s your problem? Everything that’s wrong with you is your fault. Stop blaming me. Stop complaining.’ And she says, ‘I’m in big trouble.’ And then it’s him and it’s her, and then it’s her in her mouth. And there’s something about the contraction of space from this huge welcoming hall into the body of this woman who’s his patient. Behind, as he thinks about Irma, he says, ‘why have I chosen Irma?’ He says, well, the real instigating factor behind this dream is the fact that his friend Otto had said to him, ‘She’s not quite better.’ Freud had been treating her.

So he was pissed about this. He’s also pissed about it because he’s in a position in which his authority is being undermined as a doctor because Irma is a friend of a friend who’s a doctor. This is not a good position to be in if one is going to be someone’s psychoanalyst. There’s too many ties, there’s too much pressure. He can’t just work the way he needs to. So his authority is compromised. He’s got this doctor, like, ‘What are you doing? It’s not working.’ He realizes in the dream that he prefers her friend, who he was also seeing, who was much more available, less recalcitrant, who sort of gave himself over to her more readily. And then behind this woman is his wife who’s pregnant and had recently had abdominal pains. So Irma is in fact three women. And you have three women, and you have three men.

You have Dr. M, Leopold, and Otto. So the dream is perfectly structured between these tripartite figures and you have them in a way in opposition. You have the sick women and you have the doctors who are all trying to cure the quote, ‘sick women,’ and Freud’s standing in between. And the question is, is the cure organic? Is it something medically wrong? Is it something in their bodies? Is it an infection or is it something else? What of course is this? Something else is about psychic life. It’s about language, it’s about speaking. It’s about sexual life. It’s about the body that’s not just something that lives or dies, but is something that is living and desiring. And in the process of dying, and is fraught then for Freud with questions of sexuality and sexual need. And so he’s standing there in the middle between these figures and he’s trying to hold his place.

He’s trying to hold his place at the moment that he’s trying to give birth to this science by writing this ridiculous book about dreams, right? With which he opens the entire saga. And he says, I’m going to put before you all of my anxiety, all of my desire to be the one who can cure her against these people who say what I’m doing is ridiculous. I stand here before you. There’s an amazing dream in the “Interpretation of Dreams” book where he does a dissection of his own body, right? He says, ‘This is the book; I’m here dissecting my soul in front of all of you in order to prove what it is that I believe about what it means to cure somebody.’

He also says that there’s the weight of judgment on the book for which he wants to prove himself innocent, which he calls ketologic, which is very funny. He says, the whole plea for the dream was nothing else. And reminded me vividly of the defense put forward by a man who was charged one of his neighbors with having given him back a borrowed kettle in damaged condition. The defendant asserted first that he’d given it back undamaged. Secondly, that the kettle had a hole in it when he borrowed it. And thirdly, that he had never borrowed a kettle from this neighbor at all. Any one of these would have acquitted him. So he’s trying to get out from under a kind of guilt and recrimination and find his will to stand on his own in this dream, which is what’s so kind of remarkable about it.

Now, the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan said about this dream, and he really elevated it into the heights, ‘This is a transmission through Freud to the centuries of analysts to come. This is the most important dream. This will be the dream of all dreams for all psychoanalysts to come.’ And that’s what he kind of has to say in his analysis of it. But he says, ‘Very importantly what you see in the dream is that the dream imagines the symbol. It puts symbolic discourse into a figurative form, namely the dream.’ I mean, sorry, ‘It’s an imagining of the symbol,’ right? Dreams are images. And yet when you break the dream down, it’s a whole number of symbolic forms, languages, thoughts, memories, ideas, right? And when you analyze a dream, when you finally make a dream interpretation, you take that image and you put it back into the symbolic form. What is it that you need to say to these images? What’s the thought that you need to add to the images of the dreams that you unpack?

One of the things that he says that I like very much about this is that he says, ‘Freud’s a tough cookie. He’s done a lot of work on himself. Most people, by the time they look in this woman’s mouth and they see this horrible thing that’s like a nose and that’s oozing and white and disgusting, you would wake up, you’d say, forget it. I got to get up and I got to get on with my day. I can’t think about these horrible things. But Fred keeps dreaming and he gets to go a little bit further because he’s already been working on himself.’ But the idea at this point is that he says, ‘He’s looking at the flesh from which everything exudes at the very heart of the mystery. The flesh in as much as it’s suffering is formless in as much as its form in itself is something which provokes anxiety. You are this, which is so far from you, this which is the ultimate formlessness. Freud comes upon a revelation of this type at the height of his need to see and to know which was until then expressed in the dialogue of the ego with the object.’ So he’s there, he wants to be the doctor, he wants to be a good guy, he wants to be innocent, he wants to know. He wants people to believe that he knows, he wants to prove himself. And he comes upon something that says, ‘You are nothing,’

‘You are goo,’ ‘You are destroyed,’ ‘This isn’t the path that you can take. You cannot take this ego path.’ And he survives, survives this destruction. And that’s the important part for by which he says, ‘Because he survives, he’s able to come further and he’s able to dream of the solution to Irma’s pains.’ What’s the solution? It’s this weird thing called trimethylamine, which it actually doesn’t really exist. It’s like a nonsense word. It means like, ‘3, 3, 3.’ It is involved in the decomposition products of sexual substances. So that’s what gives off the smell. It’s what gets you excited when you’re sexual. And it’s very important because one of the things that Freud said is that in humans, our hyper reliance on the visual de functionalized our noses, it’s true. It’s actually like if you look in evolutionary science, it’s true our noses work a lot less well than animals.

So we don’t smell each other’s genitals when we meet each other, we say ‘hello,’ and we try to ignore those kinds of things. But Freud was interested in this because there’s still something that sets off a process of excitement. So in the dream, you have the question of our original animal sexual excitation, what we’ve lost in the process of human civilization at the same time that what this symbol means is, at least for Lacan says, ‘It’s nothing else but the word. It’s the fact that what psychoanalysis is going to be is not a cure by sex, not a cure by medicine, but a cure by speaking. We are going to speak, we are going to read, we are going to listen, but we are going to be able to talk about everything that we want to talk about. And this is what I have to understand.

And to do this, I cannot have an ego to do so. I cannot want to be right. I cannot want to prove, I cannot want to make this woman just give me what I want her to give me. I cannot want to make these doctors believe in what I’m doing. I cannot want them not to be scared by the fact that I’m treading into this territory.’ So Lacan, nicely enough, decides that he’s going to speak for Freud in his arrogance of doing so. And he says—this is what he hears Freud saying to us—He says, ‘It isn’t just for himself that he finds the nema or the alpha omega of the acephalic subjects, which represents his unconscious. On the contrary, by means of this dream, it’s him who speaks and who realizes that telling us without having wanted to, without having recognized it at first and only recognizing it in his analysis of the dream.

That is to say, while speaking to us something which is both him and no longer him, I am he who wants to be forgiven for having dared to begin to cure these patients who until now, no one wanted to understand and whose cure was forbidden. I am he who wants not to be guilty of it, for to transgress any limit imposed upon us until now on human activity is always to be guilty. I want not to be born that. Instead of me, there are all the others. Here I am only the representative of this vast, vague movement, this quest for truth in which I have faced myself. I’m no longer anything. My ambition was greater than I, no doubt the syringe was dirty. And precisely to the extent that I desired it too much. That I’ve partook in this action, that I wanted to be myself, the creator. I am not the creator. The creator is someone greater than I. It is my unconscious. It is this voice which speaks in me and beyond me.’

Fred was so confident in his discovery that he wrote to his friend, will him place, “Do you think that one day there will be a marble tablet on the house saying in this house, the secretive dreams was revealed by Dr. Sigmund Freud?” There is a tablet on the house in Vienna. I mean, there’s something funny about, I mean, he’s such a megalo—Freud is megalomaniacal. But you have to be. You have to be to undertake something like this. And at the same time, in that megalomania, you also have to take yourself down a notch. You have to confront your limits. And there’s something amazing about this book in which you see someone doing this in real time and inventing something. And part of the idea about this show is this show as the invention, the creation of Allison with her creations, with her teachers, with her studio mates, with her friends in it, which is just the remarkable fact that some of this was around in Aspen, and the event of the show happening now—which I was saying there’s something very sad about the idea that it’s going to go away, like these pieces won’t ever see each other again.

And that quality of the event is very important in analysis. You show up at the session and you have a chance to speak, and what you say happens then. And then that’s it. You leave and it’s over, right? Every night you have a dream, you better grab it. You better grab it and understand what it’s telling you at that moment because it’ll be gone. It’s not that you won’t have another chance later on, but that moment is a unique moment.

And to see this book not as some contribution to science, but also an event in itself, I think is one of the most important ways to read, especially these beginning works of Freud, because there’s so involved in himself. Fliess was his mentor in a way. Fliess is the kind of pseudo-analyst that Freud working with. And he was writing the dreams to this guy saying, ‘Here’s what I think is going on with me.’ And the guy was a bit of a weirdo to be honest, but he just sort of said, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s good. Keep going.’ I mean, in a way that’s all he needed at that point in time, which is sometimes all you need from a mentor is to say, ‘Just keep going,’ right? ‘Keep trying to figure out what you need to figure out.’

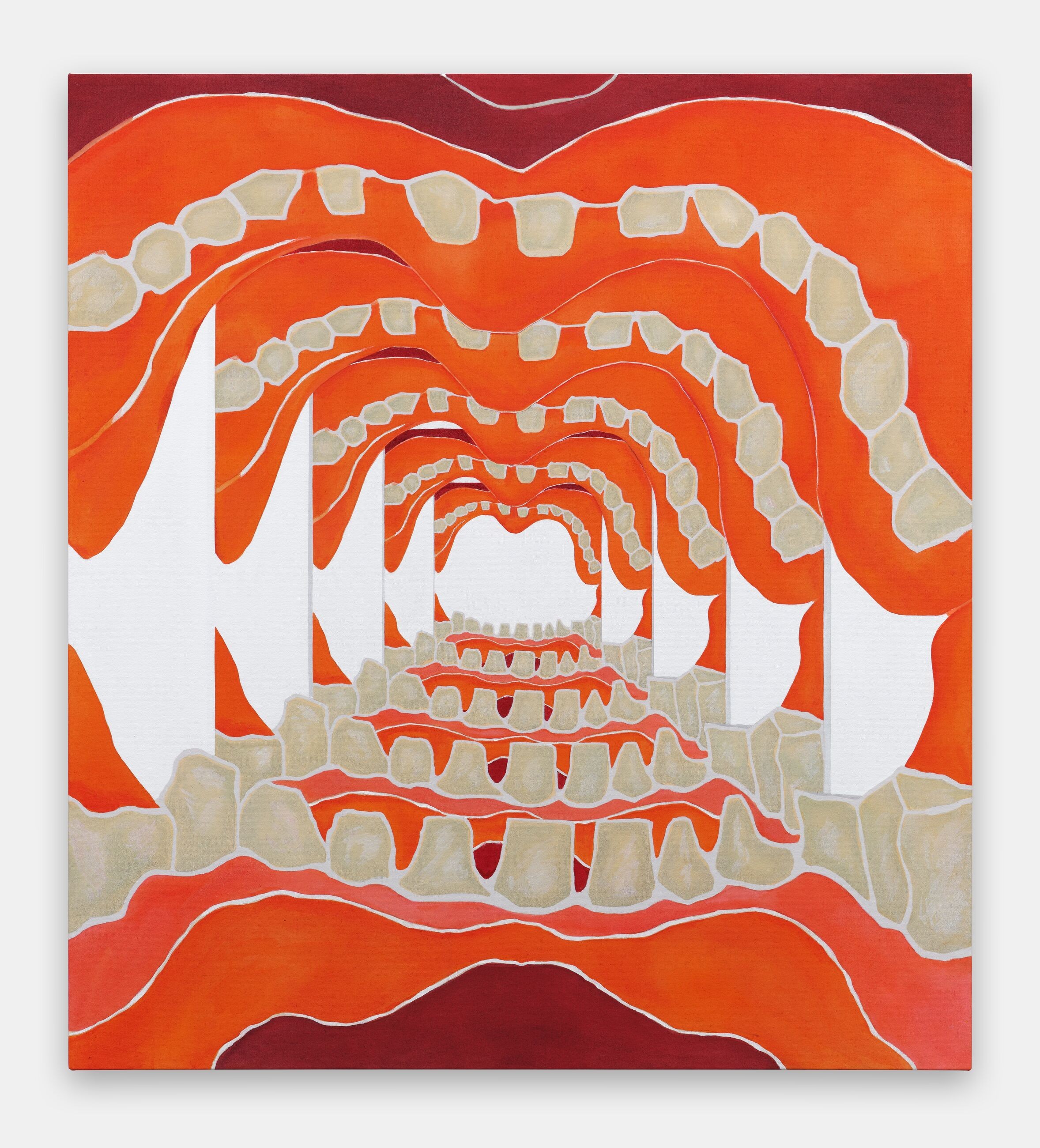

I thought it was pretty uncanny that this was Allison’s painting. So I mean, I dunno, she should rename it “The Dream of Irma’s Injection.” Alright, Destruction, Psychopathology of Everyday Life. We all know this. It’s Freudian slips of the tongue. But in fact, unlike the mistake we say, it’s not this other person, it’s my mother or whatever it is that you say that you make a mistake and you reveal something. There’s also mistakes. The mistakes that he focuses in on more than those are. In fact, when you forget things and Freud belief that all times that you forget something, there’s a motivation behind the forgetting. And that’s why I’m calling this “Destruction.” Because unlike the dream, which is a creation, there’s something about the forgetting that’s more about repression. It’s on the side of what is being dragged under, what can’t express itself, in fact. And that you see in these lacuna, in these blips, in these errors, in these bungled actions that reveal that there’s something there that won’t let itself make you have a successful action. In fact, that’s stopping you from having the action that you want to have. So this is what he wrote in 1901. And what’s interesting about this, and I’m not going to read this whole quote to you, but he says that he thinks it’s amazing that what often we forget is proper names.

There’s something about the forgetting of names—and you can see this and how important this is in Allison’s work. I mean, she obviously works with her name over and over and over again—but the forgetting of a proper name is important to him. And that also, when you forget that name, you often have to come up with all these other names around it. And if you looked at those, they eventually lead you back to the name that you forgot. So I’m going to say more about this in a minute, but this is the Inaugural Example. He says, ‘During my summer holidays, I once went for Carriage drive from the lovely city of Ragusa to a town nearby in Herzegovina. A conversation with my companion centered as was natural around the condition of the two countries, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and the character of their inhabitants. I talked about the various peculiarities of the Turks living there as I had heard them described years before by a friend and colleague who had lived among them as a doctor for many years.

A little later, our conversation turned to the subject of Italy and of pictures, and I had the occasion to recommend my companion strongly to visit Orvieto sometime in order to see the frescoes there of the end of the world and the last judgment, which was one of the chapels in the cathedral that had been decorated by a great artist. But the artist’s name escaped me, and I could not recall it. I exerted my powers of recollection, made all the details of the day I spent in Orvieto, pass before my memory and convinced myself that not the smallest part of it had been obliterated or become indistinct. On the contrary, I was able to conjure up the pictures with greater sensory vividness than is usual with me. I saw before my eyes with a special sharpness, the artist’s self-portrait with a serious face and folded hands, which he had put in a corner of one of the pictures next to the portrait of his predecessor in the work Fra Angelico Fiesole.

But the artist’s name ordinarily so familiar to me, remained obstinately in hiding, nor could my traveling companion help me out. My continued efforts met with no success beyond bringing up the names of two other artists who I knew were not the right ones, Botticelli and Boltrafio, the repetition of the sound and the two substitute names might perhaps have led a novice to suppose that it belonged to the missing name as well. But I took good care to steer clear of that expectation. Since I had no access to any reference books, I had for several days put up with this lapse of memory with inner torment at frequent intervals each day until I fell in with an accultivated Italian who freed me by telling me the name Signorelli. I was myself able to add the artist’s first name, Luca. And soon my ultra clear memory of the master’s features as depicted in this portrait faded away. What influence had led me to forget the name Signorelli, which was so familiar to me and which was so easily impressed on the memory? And, what paths had led to its replacement by the names Botticelli and Boltrafio?’ And so this is what he is going to start the book with, and he’s going to show you all of the connections.

What’s interesting about this is that he first does the work around the B–O signifier. So Bosnia, obviously, is important in that. You have the two artists with the B–O, and you have Bosnia. (Actually, I’m going to put this up for you first. One second…isn’t this great?) And part of what he says that was coming up right before he forgot the name—what they were talking about with respect to Bosnia—was the way that the doctors behave in that country. So one of the things that they said was, that when you come to a patient and you say, ‘There’s nothing more I can do for this person, they’re going to pass.’ They say, ‘Heir doctor, you need not say more. I know you’ve done everything that you can do.’

Now, part of what Freud is reminiscing about when he’s reminiscing about this is the fact that the doctor’s given a kind of priest-like authority, right? I mean, you put your hands into the hands of the priest, you put yourself into the hands of the doctor, and you thank them for the work that they do for you. This is certainly something that’s on the wane at the point in time in which Freud’s working: 1901. One does not have that kind of authority. And as we said with ‘The Dream of Irma’s Injection,’ Freud’s wondering about what kind of authority he can have as a psychoanalyst who wants to address questions of the unconscious and sexual matters, right? And at the same time, he must have some kind of authority in order to engage in this conversation with people about their lives, about the most intimate matters. So something about this already was stirring something up that was foregrounding the subsequent repression of the name Signorelli. The second thing that came up apparently about Bosnia, which he said, it took him some time to remember, was that the second thing they said is that they love sex. And that one of his friends recall that someone said to him, ‘Heir Doctor,’ because he was having a sexual problem, ‘if I can’t do that, I’d rather not live.’ So Freud says, straight away, we were already in the terrain of ‘sex and death,’ and this terrain was setting the ground for what it was that he was going to repress.

What’s amazing is that he says that the ‘heir’ in this ‘Heir Doctor,’ which kept coming up in the appeal that these people would make to the doctor has, of course the ‘signore’ and it. ‘Heir’ is a translation in German of ‘signore’ in Italian, and Freud says he himself always made these German Italian transitions and translations in his own mind. So he does all of this and he says, ‘Okay, everything makes sense: You’ve got Herzegovina, you’ve got Bosnia, you’ve got the 'bo–,’ you have the ‘heir,’ you have the ‘signore.’ We can see where all of this is working together.‘ He says, 'But I’m going to go a little bit further.’ He goes, ‘Because it doesn’t make sense to me that this word, 'Boltrafio,’ it doesn’t really seem to fit. The ‘–elli’ works with Signorelli, but this seems to be its own production that must be accounted for.‘

So then he remembers that he had gotten news two weeks before from Trafoi—which is very similar to 'Boltrafio'—and the news that he had gotten—which he had certainly not wanted to think about since—was that a patient of his had committed suicide because he was impotent. And this distressed him greatly. So once again, you have a question of the failure of the cure, the desire to be the one who finds the cure for the mysteries of life, right behind the forgetting of the dream with all of the questions of the judgment. And of course then he says, 'Oh, the “Last Judgment,”’ right? The painting: “The Last Judgment,” the End of the World, the Apocalypse.

So all of the elements of the Irma dream are present in this amazing forgetting of the painter, Signorelli. And I loved looking at these images. (I dunno, unfortunately that’s so pixelated.) But this is what Freud saw with immense clarity when he couldn’t remember the name and all of this history behind the forgetting of Signorelli and the question of what this meant for him at the place that he was standing at that point in time at that precipice. And here’s the painter with his hands folded seriously. It’s very interesting because Ford always had to have a male companion and his life. No, he always had to. And then he loved them and he hated them and he fought with them and so on and so forth. So it’s interesting that this is also what he saw with such immense clarity. And I love the quality of his—when he speaks about the example that he’s looking at the vividness and the fading as if these things are coming in and out of the unconscious against his own will. And that was always what he was attentive to; the details of what you can suddenly see and then the way that you can’t see all of a sudden, what you can remember so clearly and then what you can’t remember all of a sudden.

So just to think a little bit about Allison, of course, again, here’s a painting with her name and I loved this. It’s also the Last Judgment in the Apocalypse—which is in the room—which is the sort of sexual room, the dark room, the denizens. She calls it, “Someone Else’s Dream.” And then this—which I think it’s funny that it’s in the kitchen—but you don’t know, especially with the context of Pompeii, whether this is a sexual scene or whether it’s a scene of dead bodies. And so this question of ‘sex or death’ that lingers in the background.

Alright, so that’s Forgetting. Imagine if every time we forgot something, we sat and we did this. Who is the time? The last one stumped me a little bit. I mean, I’m going to talk about Jokes for a second. The jokes in the joke book aren’t funny, like 1905, I guess we don’t get their jokes anymore, but it’s a really wonderful book to read. And to the jokes, I just want to add hysterical symptoms because that’s also where Freud started. So in the very beginning, he was always working with these women and their symptoms, and the symptom for him was a creation. So those are the last two things I’m going to talk about.

Before we start. I just want to say about part of what you saw in the Forgetting is the way that language is broken into pieces—Freud actually calls them ruins; that you see the ‘bo–’ and the –ellie and the –trafil. I mean, words are broken pieces that we just put together like this. And so you see how language breaks apart into a million pieces, almost like an explosion in the Forgetting, to find the word that exists in its entirety, that’s hidden in the unconscious—you have to sort through these ruins. with jokes. We condense words, we make puns where we put two words together or we make a word mean something else. We’re playing with the words in their entirety and we’re making them resound. We’re making them into new creations. We’re making witticisms, as it were. And this is very important because you see two sides: you see the capacity of language to create, and you see the parts of language that are always in the process of being destroyed. The other thing that he says about jokes is that they are to be transmitted. So unlike dreams, which it’s your own dream, and Freud thought that dreams were incredibly asocial. In fact, they don’t make sense to anyone. No one wants to listen to your dream. You start talking about it and everyone’s eyes glaze over. They’re not for someone else, but a joke is always written to be told and to be told again and again and again. So he says it’s the most social formation of the unconscious. And when you make a joke or when you hear a joke, you immediately think, ‘Oh, who am I going to tell that to?’ Right? So you’re in the mode of wanting to spread it virally, like a meme.

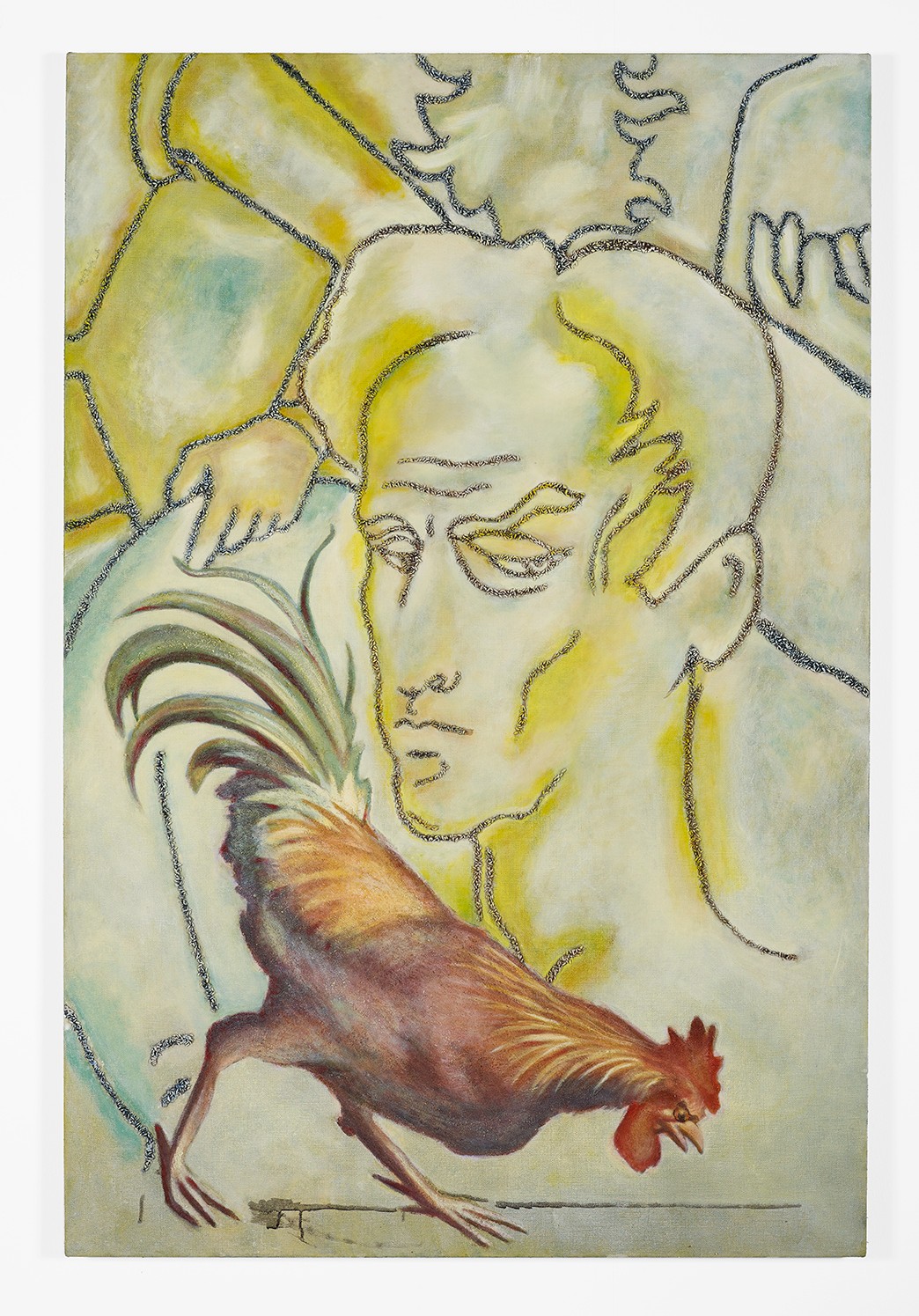

And he loved it for this. And he was also very interested in the fact that it transmits something. It transmits what’s funny at a given point in time because of judgments and prohibitions, because a joke transgresses those, a joke always transgresses what is prohibited at any given cultural moment. And he says that it kind of sneaks past the sensor. And what’s amazing about that ‘sneaking past the sensor’ is that part of the way that it sneaks past it is that you laugh before you consciously understand what’s funny, right? And only later then you put, ‘Oh, that’s so funny, and I this, and this, and that,’ and you only understand later. And that’s how it sneaks. And he loves it also because part of this sneaking is via pleasure: by giving you pleasure without consciousness of what’s pleasing you. It has very much the quality of Allison’s kitchen room, which is—no, I mean of all the rooms, it’s very funny and it’s very weird, and it’s like the strangest combinations of things. And of course she has the hearth fire—and I’ll show you later, I have her painting—but the cock painting is in there, which is obviously one of her jokes that she’s telling throughout her ouvre. So this is for it’s joke.

This is from Hina: he says, ‘Hina introduces the delightful figure of the lottery agent and extractor of Kornshirsch Hyacinth of Hamburg, who boasts the poet of his relations with the wealthy Baron Rothschild. And finally says, and true is God shall grant me all good things, 'Doctor, I sat beside Solomon Rothschild and he treated me quite as his equal, quite familionarily.’ So he loves this because it’s a condensed word. And the joke is both that he combined familiar and millionaire: ‘familionarily.’ Freud says it’s like his other favorite joke, which is the ‘alcoholidays.’ That one’s more funny, I think.

And here he’s showing how the condensation works. So your unconscious does this, right? I mean, when you make a joke, you find these elements and you condense them perfectly into the possibility of a new word. And actually, if you look at the history of linguistics, linguistics always says this. I mean, the way that languages evolve and develop and create themselves is that you find these easy ways in which to combine things, which are all of the new idioms, all of the new words, all of the neologisms that we create. One of the things about patients who are “schizophrenic” or “psychotic” is that they have the most incredible, incredible capacity for neologism-making because they’re closer to the unconscious, as it were. We can only do it when we concentrate and make a joke, or we only do it in our dreams, but they just do it naturally. They make them all the time. This is the reason that Jacques Lacan said that we should hang out with psychotic people or we should allow psychotic people to be amongst us because they’re the most creative to a certain extent with language and ideas. Obviously there’s a great tradition in art making of outsider art or artists who are, whatever, “on the edge,” as it were.

So you see this in the joke. So Freud says, brevity is the soul of wit, and that’s the way that jokes work. They find something and they find the direct path. Condensation works with composite words, with modification, multiple use of the same material and parts in different orders, double meanings, double entendres and various illusions. So he’s showing that this is how wit works and why we’re witty, and it takes the unconscious to do this for us. So this is in her kitchen, this is her cock painting. She has the cock and she has ‘cocteau,’ and she paints these with rice—It’s really amazing to see in person.

And also this: I hadn’t quite realized when I was looking at the show that that wall is called “the Transmission Wall.” I wish I—I saw this as ‘transmission’ and the ‘verbal transmission’ and the question of the ‘joke.’ But she also has that incredible Pompeii fragment that almost looks so modern. It looks like it’s a TV screen or a computer. And then she has the TV sculpture on the side. So she saw that as her ‘Transmission Triptych’ across time. Alright, and just the last one, which is, so Freud, in 1905, also wrote “Fragment of Analysis of a Case of Hysteria.” This is the famous Dora case. It’s the only case of a woman that he wrote. And what’s amazing about this woman is she’s like a version of Irma is the case that he presents of a hysterical patient is a failed case. He had many successful cases at that point, but he gave us a failed case in which he one hundred percent slices Freud at the knees.

She says, ‘You know what?’ Because he wanted to cure her so badly, and he wanted to be the one who knew all the answers. And she was like, ‘Forget it. You’re just like all the rest of these people. Like, I’m out of here.’ And she blew out of the treatment in six months. But, I think that he did restore to her a degree of dignity because she was able to tell her story about what was going on with her and her life. And all of her minor hysterical pains went away over the course of the time in those six months of treatment. One of the things that’s amazing about this case is that it’s highly involved in pictures. The very last dream that she has references some—I don’t know, six, seven paintings—up to the final one, which I’m going to show you, which is the “Dres in Madonna.” So, there’s this incredible relationship to culture, to painting, to what everyone was looking at that’s behind all of these examples in this relationship between the image and the symbol.

I just wanted to read this because the last part of Allison’s show is the “Gradiva,” and the question of what it means to walk on all of this creation and destruction or walk through it or survive it or live with it and have it exist around you. And this is what Lacan says about neurosis: he says, ‘Neurosis is not identical to an object. It’s not a parasite foreign to the personality of the subject. It’s an analytic structure which is in your acts and your conduct. Progress in our conception of neurosis has shown that it’s not only made up of symptoms that are decomposable into their elements, the signifiers, but that the entire personality of the subject bears the mark of these structural relationships in the way it’s employed here, the word personality goes well beyond its primary acceptation with what that comprises. That is static and confluent with what is called character. It’s not that. It’s personality in the sense in which it designates in behavior, in relationships with the other and with others. A certain movement that is always found to be the same: a scansion, a certain way of moving from the other to the other, and moreover, to an other that is always an endlessly being refound and forming the very variations of obsessional actions.’ So he’s saying that we often have the idea of our character as who we are as a fixed idea, but it’s in fact all of this that moves through us and our way of being with that movement that we each have a unique way of moving with that. That one might want to call neurosis. Now, neurosis is often thought of where you get stuck, the things that you can’t stop doing where you have a compulsion or where you have insisting pains that just keep happening, what repeats in your life. But this is the way that all of this material is moving through you and that psychoanalysis tries to help you move with it.

And so there’s something very beautiful about the fact that I think she ends the show with this addenda. That’s the Gradiva figure. And so I wanted to show you this: so Dora, at the very end of her treatment, stares at this painting for two and a half hours and doesn’t know why. And Freud—who’s an idiot—didn’t ask her why. But what’s amazing about this painting is I think some of the speculations about it was that it was placed across from the altar in the church—the church burnt down, so we don’t know—but, she’s looking at her son who’s going to die. And that explains the look on her face, which isn’t quite the beatitude of the Madonna with child, but something with an apprehension and worry about the future. But, what’s also thought about so beautiful is not just the curtain structure, which you also see in Allison’s show at various moments, but the stepping forward into the future, the stepping forward into the frame, that there’s something very much about this painting, which is her moving.

I’ll just contrast that with Allison’s painting and I’ll leave you guys to your Saturday. I’ll stop there. Thank you.

free courtesy

Amy & John Phelan

- Aspen Art Museum

- 637 East Hyman Avenue

- Aspen, Colorado 81611

- t: 970.925.8050

- f: 970.925.8054

- info@aspenartmuseum.org

| Hours |

|

Tuesday–Sunday, 10 AM–6 PM

Closed Mondays

|

© 2024 Aspen Art Museum

General operating support is provided by Colorado Creative Industries. CCI and its activities are made possible through an annual appropriation from the Colorado General Assembly and federal funds from the National Endowment for the Arts.

General operating support is provided by Colorado Creative Industries. CCI and its activities are made possible through an annual appropriation from the Colorado General Assembly and federal funds from the National Endowment for the Arts.